In the pragmatic world of New York City real estate, where every square foot is meticulously accounted for, a curious architectural omission persists. Step into an elevator in many of the city's residential high-rises, and you'll often see the floor numbers jump directly from 12 to 14. The 13th floor, it seems, has simply vanished.

This isn't a structural anomaly but a deliberate choice rooted in a centuries-old superstition. A recent study of over 600 residential buildings in New York City found that more than 90% of them do not have a floor officially labeled as the 13th. For developers and landlords, the decision isn't about belief; it's about business.

Key Takeaways

- Over 90% of New York City residential buildings with more than 13 stories omit a labeled 13th floor.

- The practice is driven by triskaidekaphobia, the fear of the number 13, and developers' concerns about spooking potential buyers or renters.

- Instead of a 13th floor, buildings often label it as "14," "12A," or use it for mechanical equipment.

- While historically widespread, some newer developments are beginning to include the 13th floor as cultural attitudes shift.

A Citywide Custom

The absence of the 13th floor is a well-established custom in New York's vertical landscape. While the floor physically exists, it is almost never designated as such on elevator panels or in rental agreements. A 2020 analysis by StreetEasy examined 629 residential buildings and discovered that only 55 of them—a mere 9%—had a button for the 13th floor.

This phenomenon extends beyond residential properties. Otis Elevators, a major manufacturer, estimated in 2002 that around 85% of the elevators it serviced did not include a button for the 13th floor. Iconic buildings like the Empire State Building and One World Trade Center are exceptions, but for most developers, avoiding the number is standard practice.

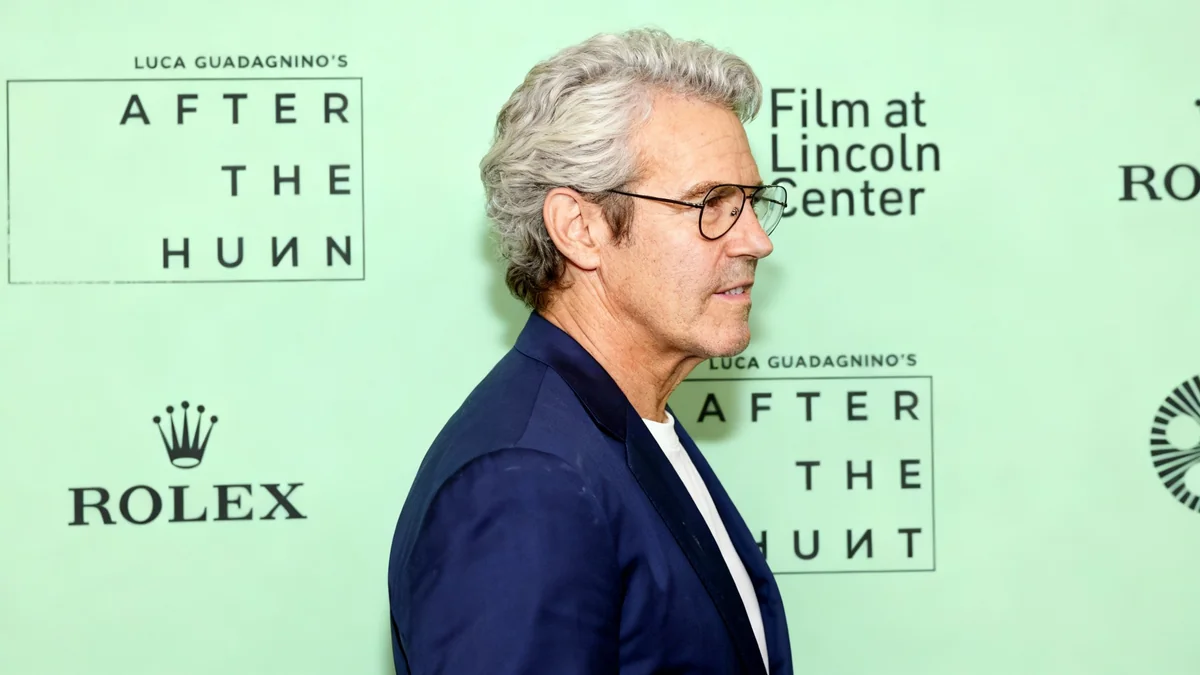

Television personality Andy Cohen recently highlighted this quirk when selling his West Village duplex. His apartment occupied the 12th and 14th floors of his building. "I lived on 12 and 14 and it was weird enough for me to get my head around it," Cohen noted, adding that "14 sounds better than 13."

By the Numbers

A study of 629 NYC residential buildings taller than 13 stories found that only 9% officially labeled a 13th floor. The other 91% either skipped the number or disguised the floor with a different name.

The Economics of Superstition

The driving force behind this architectural tradition is not fear, but finance. Developers and landlords are acutely aware that any factor, however irrational, could deter a potential tenant or buyer from signing a lease or closing a deal. The fear of the number 13, known as triskaidekaphobia, is a risk they are unwilling to take.

"From the point of view of any builder, the owner is interested in renting the space, and he doesn’t want anything to get in the way of that. So 13 goes out the window," explained Andrew Alpern, an architectural historian specializing in New York apartment houses.

This business-first approach means that even a small percentage of superstitious clients could translate into significant financial losses. In a market as competitive as New York's, eliminating any potential objection is paramount.

"I think that people have so much anxiety... about undertaking anything that might be considered bad luck with a real estate investment, that adding a single thing to that fear pile is never worth it," said Corcoran broker Sydney Blumstein.

Historical Roots and Modern Problems

The fear of the number 13 has debated origins, with some pointing to the Last Supper, where Judas was the 13th guest, while others cite Norse mythology. Regardless of its source, the superstition became embedded in Western culture and eventually influenced urban development as buildings grew taller.

A Skyscraper Problem

The issue only became prevalent as technology allowed buildings to surpass 13 stories. According to Sam Hightower, director at the Office for Metropolitan History, this was a gradual process. In 1900, only two building permits were filed for structures of that height. By 1915, that number had grown to 28, making the "13th floor problem" a more common consideration for developers.

While developers make the change for marketing purposes, the discrepancy between architectural plans and public-facing floor numbers can create confusion. Architectural plans filed with the Department of Buildings label floors sequentially, including the 13th. The marketing name is a separate decision.

This can cause practical issues. Historians find it frustrating when trying to accurately document a building's structure. More critically, it can create confusion for emergency responders or delivery services who may have to reconcile different floor counts. In 2015, the city of Vancouver, Canada, went so far as to ban the practice of skipping floor numbers to avoid such problems.

A Shift in Perspective?

Despite the long-standing tradition, there are signs that attitudes may be changing. Some modern developers are choosing to include the 13th floor, viewing the old superstition as outdated. This shift reflects a broader cultural trend of reclaiming symbols once considered unlucky.

"I’ve seen 13 on many buildings recently," Blumstein observed. "I feel like the reclaiming of things that people previously thought were superstitious has been like a big ownership in the information era, and it’s kind of like a badge of honor — like, ‘Yeah, I live on 13.’"

Still, she acknowledges that logic doesn't always drive real estate decisions. Whenever she shows a unit on a 14th floor that is actually the 13th, she makes a point of informing her clients. For now, the practice of skipping the number remains the dominant trend.

As historian Andrew Alpern concluded, the custom may seem illogical, but its impact is tangible. "I think the whole thing’s quite silly," he said. "But from the landlord’s point of view, it’s very real. If he loses any potential renters, that could cost him money and he doesn’t want to do that."