A federal court has allowed a lawsuit to proceed against the state of Nevada over a law that requires real estate brokers to maintain a physical office within the state. The case, brought by a New Jersey-based broker, argues that the requirement is an unconstitutional barrier to interstate commerce in an era of increasingly virtual business operations.

The U.S. District Court for the District of Nevada recently denied the state's motion to dismiss the core claims of the lawsuit. This decision means the legal challenge, which contends the law unfairly protects local businesses from out-of-state competition, will move forward, potentially setting a precedent for how states regulate remote businesses.

Key Takeaways

- A federal court denied Nevada's request to dismiss a lawsuit challenging its real estate broker laws.

- The law requires brokers, even those licensed in Nevada, to have a physical in-state office.

- The plaintiff, Derek Eisenberg, operates a virtual real estate business and is licensed in 26 states, including Nevada.

- The lawsuit argues the law violates the U.S. Constitution's dormant Commerce Clause by restricting interstate business.

A Modern Business Model Clashes with State Regulations

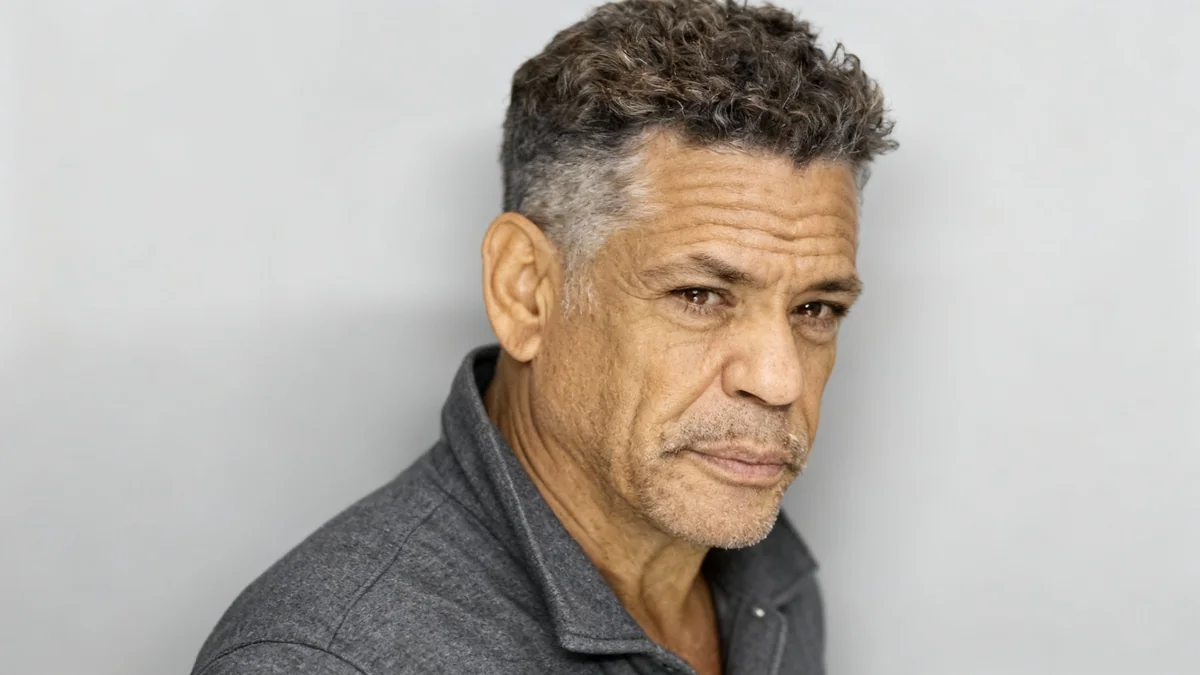

At the center of the dispute is Derek Eisenberg, a real estate entrepreneur from New Jersey. Since 1995, his company, Continental Real Estate Group, Inc., has built a business model centered on virtual services. This approach allows his team to offer flexible and often more affordable real estate services across the country.

Eisenberg holds real estate licenses in 26 states, and his company's employees are collectively licensed in 42 states. This extensive network enables them to serve a broad national market without being tied to a specific physical location for each state's operations.

However, Nevada's regulatory framework presents a significant obstacle to this model. The state has specific rules for licensed real estate brokers that directly conflict with a virtual-first approach.

Nevada's Requirements for Real Estate Brokers

Under current state law, a licensed real estate broker must:

- Maintain a physical, in-state office.

- Transact all authorized business from that specific office.

- Keep and maintain adequate records at the in-state location.

These rules effectively prohibit Eisenberg from operating in Nevada as he does in other states. To comply, he would need to establish and staff a brick-and-mortar office, a move that undermines the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of his virtual business model.

The Constitutional Question at Stake

The lawsuit, Eisenberg v. Sanchez, targets the Nevada Department of Business and Industry and the Nevada Real Estate Commission. The central legal argument rests on a concept known as the dormant Commerce Clause.

What is the Dormant Commerce Clause?

The Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution gives Congress the power to regulate commerce among the states. The "dormant" aspect is a legal doctrine that courts have inferred from this clause. It prohibits individual states from passing legislation that excessively burdens or discriminates against interstate commerce, even when Congress hasn't acted on the specific issue.

Eisenberg's legal team, from the Pacific Legal Foundation, argues that Nevada's in-state office requirement does exactly that. They contend it creates an unfair advantage for local brokers by shielding them from out-of-state competitors who leverage technology to offer services differently.

"The Constitution gives entrepreneurs and business owners the right to work across state lines," the foundation has stated in relation to similar cases. They argue that requiring a physical office hurts not only business owners with non-traditional models but also limits choices and opportunities for consumers.

The state of Nevada sought to have the case dismissed, but the district court's recent ruling found that Eisenberg had plausibly shown that the government's actions could be a violation of his rights. The case will now proceed to examine the merits of this central constitutional claim.

Broader Implications for Remote Work and Interstate Business

While this case focuses on real estate in Nevada, its outcome could have far-reaching consequences. The rise of remote work and digital services has blurred traditional state boundaries for many professions. The legal question is whether state-level regulations, often created decades ago, can be used to prevent modern, technology-driven businesses from competing across state lines.

If the court ultimately sides with Eisenberg, it could challenge similar protectionist laws in other states and industries. Proponents of such a change argue it would foster greater competition, potentially leading to more innovation and lower prices for consumers.

On the other hand, states often defend these regulations as necessary for consumer protection, ensuring that regulators have physical access to business records and a clear point of contact for oversight and accountability. The court will have to weigh Nevada's stated purpose for the regulations against the burden they place on out-of-state businesses.

What Happens Next?

With the motion to dismiss denied, the case now moves into the discovery phase, where both sides will gather evidence and build their arguments. The court will eventually determine whether Nevada’s law serves a legitimate local purpose that cannot be achieved through less burdensome means or if it is primarily an unconstitutional barrier to free trade among the states.

The final decision will be closely watched by entrepreneurs, regulators, and consumers alike, as it touches upon the fundamental right to earn a living and participate in the national economy, regardless of physical location.